Writers would quit writing if they wrote for the reader. Readers who sit or lie while reading to satisfy something inside, a voice that beckons in whisper (whimper). If the writer cared for the reader and wrote in the best interests of the reader, he/she would quit writing and instead pick up the pen as a weapon in defense of the reader, to subdue the approaching monsters, namely literature and other writers who have not yet surrendered the pen for the sword, because the writer who writes with the reader in mind writes (different from the previous verb but nonetheless a verb that shall heretofore be referred to as write) for capital gain and fame, which are both diametrically opposed to literature, except in extreme circumstances. Writers are most often broke and unwilling to write for the reader and instead cater to that obsession within, not a voice, not a whisper nor a whimper but a commanding shout with a throat hoarse and desperate and maligned. The writer (among the rest of the world) knows that writing is not lucrative, again, except in extreme circumstances, and the writer does not care, just as he/she does not care for whom, if anyone, ever, will read what they write. The words beckoned forth from caverns deep and resoundingly unique, the only true self, the unadorned self, the self wrapped tightly (safely) in the selfsame ideas that will ultimately destroy the self. This self obliges willingly, acutely aware of the danger and ecstasy involved.

Category: writing

-

Re-immersionalist

Perhaps I should manage my time better, become a minimalist, an incrementalist, a fractalist, a post-modern deconstructionist, for there is always so much to accomplish in one day, and so the days adhere to form an unbreakable chain upon waking from the banality and the obligation and rote pattern of it all; when we re-immerse the self back into the ever-changing world we find new patterns that must be mastered, and soon, for there is no time to waste.

-

Luna silenciosa

The moon is full and white and he watches it hang static and alone in the sky like a beacon to worlds ancient and afar. A breeze warm and comforting carries the cigar smoke away from his face and he breathes in the night air, floral, dense, fecund. Wade is at relative peace, adrift in the cosmos. Crickets and other night insects shriek in rhythm from the shadows. Direll jumps over the back fence and ambles toward Wade in the moonlight, his hand raised in greeting.

How’s your eye? Wade says.

Still cain’t see shit out of it.

Direll sits next to Wade and exhales deeply. He takes a plastic lighter from his shirt pocket and lights a joint. Wade puffs his cigar and the men sit silent listening to the crickets and also sounds they can’t hear.

Pretty moon tonight.

Reminds me of when I was a kid, Wade says.

How so?

Not sure. Stimulates something vestal, I think.

Vestal?

Maternal, maybe.

The men are silent.

Beautiful, though, Wade says.

Yeah.

Seen your Comanche pal tonight? Direll asks, smiling. He puffs long and deep on the joint and blows out what appears to Wade to be an impossible quantity of smoke, a long uninterrupted ribbon.

He’s Patwin. And no.

Insects resound in the thicket of brush to their left. The sky is open to everything. The sliding door slips open and the boy peeks out at them.

Can I play one more before bed? he asks.

Say hello to Direll.

Hi Direll.

Hello champ.

One more round of what? Wade asks.

Death Membrane.

Death Membrane, Direll repeats, looking out over the yard as if out at sea or as if he could see the words there in the half-light. As if the words or the game itself fashioned up from the underworld or vapor. The joint is tucked away out of the boy’s view.

One more round, Wade says, and the boy is back inside.

The men are silent and the moon glows as if from within and Direlle exhales sharply and says, You watch that game tonight?

Wade looks at him and puffs his cigar. No, he says. I was reading.

What you reading now.

Wade puffs on the cigar and says, Fukuyama.

Fukuyama, Direll repeats, nodding, staring at the yard again and the shadows therein.

Then they’re silent for many minutes, both of them chasing certain and uncertain thoughts. Direll tosses the roach into the grass and sighs. He says, Brother, I got to be going.

Wade watches his neighbor walk to the fence and climb over. He looks up at the moon and stares at it, wondering about it. He tamps out his cigar and stands and walks inside, the crickets announcing his departure.

-

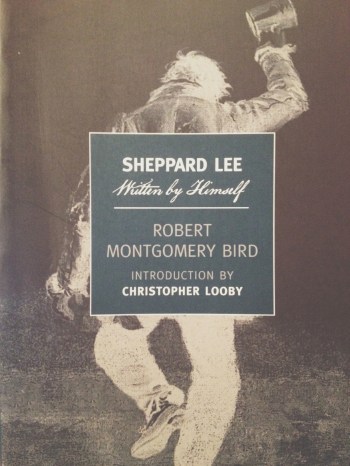

Sheppard Lee: A study in Contradiction [Review]

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness …[1]

Robert Montgomery Bird was 30 years old when Sheppard Lee was published. He’d had plenty of time to scrutinize the human condition, its psychology, and its reaction to and formulation of political structures. He observed the American men and women of his time, the deep social rifts between them, rampant envy and resentment resulting from their differences. He saw the social division as a natural reaction to the American structure, an inherent flaw in the ideals of the Constitutionalists. What resulted, according to Bird, was a society of longing, a desire to strip away one’s identity in search for another. In Sheppard Lee, Written By Himself, published by the acclaimed NYRB Classics, Bird explores these topics and castigates them with comic, satirical brilliance.

When Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, he and the Constitutionalists had in mind a particular end for the individual in a democracy. The idea was to give each individual the right to become their own end via the means they chose for themselves. The rich and the poor alike were given the political freedom to follow their dreams, to self-sustain beneath the umbrella of U.S. government protection. These were the ideas wrought from the Enlightenment, from hundreds of years of political and moral theory, and it was considered to be the best government structure—in principle and practice—in the history of the world. The policies were meritocratic and experimental in nature, molded from the idea that there is no nobler role of government than to allow its citizens the opportunity to safely and responsibly forge their own path in the world.

But what Jefferson and the other Constitutionalists failed to account for was the huge rift that would be created between the rich and poor, “a political complexion […] founded in, and perpetuated by, the folly of the richer classes.”[2] The economic structure was fashioned from the principle of equal opportunity, but what resulted was the rich becoming richer and the poor becoming poorer. Soon the opportunities of the wealthy greatly outnumbered those of the impoverished. This great division among people that were supposed to share an equal place in society created disparate perceptions: “The poor man in America, feels himself, in a political view, as he really is, the equal of the millionaire; but this very consciousness of equality adds bitterness to the actual sense of inferiority, which the richer and rather more fortunate do their best […] to keep alive.”[3]

This situation cultivated a deep and pervading sense of longing unto the poorer classes, the immigrants, the African-Americans. It was a hypocrisy that spawned indignation, for certain injustices were happening in America, the land where every man was supposed to be self-evidently equal, where this sort of unfairness ought not to have been happening. Citizens on the unfortunate side of the socio-political structure were cast further out, excluded from the decision-making process, left only to appeal, “Why should the folly of a feudal aristocracy prevail under the shadow of a purely democratic government?”[4] They found themselves wishing more and more to inhabit the lives of the privileged, hoping to inherit their advantages. The character of Sheppard Lee finds a cosmic loophole where this is actually possible for him, and what results is an absurd waltz into the American psyche where nothing, including the principles of his country, is what he thought it would be.

Slavery was obviously another American hypocrisy. In a land where all men were supposed to have legitimate opportunities for freedom and the American ideal, certain men and women were being bought and sold, treated sub-humanely, their happiness stripped from them before they had a chance to obtain it. To be a slave was to be “the victim of fortune, […] the exemplar of wretchedness, the true repository of all the griefs that can afflict a human being.”[5] These are not descriptions of equality. Bird was aware of the hypocrisy around him. He knew that the real America was a blatant contradiction to the ideals penned in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. Sheppard Lee is Bird’s response to what he observed. It’s an attack on the life around him, highlighting the absurdities in order to draw attention to them, a picaresque adaptation of reality.

e He The hypocrisy of the political structure birthed a certain behavior in its citizens. It provoked lasting looks of envy from the poor onto the rich, from the slave unto the free man, it widened the gap between neighbor and friend. It forced people into constant comparative qualification. Equality of opportunity naturally evolved into a sort of Darwinian culture where the weaker or less qualified individuals were exploited by those gaining power with each business day, each acquisition. The character of Sheppard Lee is a symbol of the common American man. He is constantly in pursuit of curing what ails him, namely his imperfections, his insecurities. He feels that the only way to do this, once he has figured out his ability to occupy the bodies of the dead, is to seek out those unfortunate dead whose lives seemed to be better or happier than his. Lee is thus vicariously the jolly hunter, the playboy, the rich man, the morally perfect human being.

As the philanthropist character in Book V begins to see his life of charity and compassion unravel before him due to the ingratitude of his fellow men, he states rather profoundly that “man is an unthankful animal, and of such rare inconsistency of temper, that he seldom forgoes the opportunity to punish the virtue which he so loudly applauds.”[6] One could read this passage straightforwardly as it applies to the narrative, or they could also read it as an analogy about the duplicity in the principles of the United States that Bird observed and attacked. At this point in the book, the reader is well aware of Bird’s pattern of disappointing Sheppard Lee’s efforts at finally becoming content with who he is, whoever that may be. The fact that he is repeatedly upset in his effort to find happiness by infiltrating the body of the most morally pure dead person he could imagine leaves him to believe that, “I had experienced in my present adventure […] doubts as to the reality of any human happiness.”[7]

Bird had keen observational skills to see the contradictions between those engraved in the United States Constitution and the actual daily social rigors in young America. But these things could have been seen even by those who chose to turn their attention from them. I might even make the argument that the rift between the haves and the have-nots is today considerably wider than in Bird’s America.

The novelist’s value in a society is his or her ability to shape and influence the culture. Bird did this by drawing attention to the inconsistencies in his society, pointing the finger at the innate hypocrisy in American idealism. He saw the way social stratification affected the individual in society and diluted their notions of identity, how it forced them to look at others in either envy or disgust. In Sheppard Lee, Bird exercised his acute understanding of the impractical democratic experiment and its effects, primarily the “political evils which demagoguism, agrarianism, […] and all other isms of vulgar stamp [it] brought upon the land.”[8]

What we see in Sheppard Lee, through Bird’s narrative about the blurred notion of identity, is a man chasing his preconceived notions of happiness, jumping from social status to social status in the pursuit of happiness, only to find something wrong, something to lament about his new body and personage with each new identity. It is a narrative both funny and sad, both audacious and absurd, and at times a promotion of prejudice as equally contradictory to the truth as Bird’s America.

[1] Jefferson, Thomas, in Koch, Adrienne. The American Enlightenment. George Brazillier Press, New York, 1965, 378. [2] Bird, Robert Montgomery. Sheppard Lee, Written By Himself. New York Review of Books, New York, 2008, 305. [3] Bird, 306. [4] Bird, 306. [5] Bird, 332. [6] Bird, 271. [7] Bird, 304. [8] Bird, Robert Montgomery, 306.

-

Yearning

When I left the library rolling skies befell the world and rain boiled downward from molten clouds sending pedestrians and anyone not under cover of shelter skittering into shadows beneath dripping awnings or back into campus buildings to avoid the onslaught of water and hail the size of human eyes hard as rock and jaggedly imperfect. I made it to the car gasping and wild in the eye with the books stuffed up into my jacket to keep them dry or as dry as possible with water pounding the roof of the car and sliding down the windows in cascades of prismatic light and sound. A strange sense of isolation and security overcame me and it was warm in the car, the windows began fogging almost immediately from the moisture in my clothes, in my hair. I sat there a long time listening to the rain reclined in my seat, eyes closed, trying to immerse myself into the water, trying to imagine myself in each ounce, in each drop of water and ice from the sky and the storm would surge and then taper off, surge and taper off, rhythmic serenity, a paroxysm of peacefulness. I could die right now, I thought, even though it was the first time all day I hadn’t yearned to die. The rain slowed and eventually stopped and again I felt part of the world, less secure, exposed afresh to the discrimination of energies and of the minds of all the people of the world and I started the car and pulled into traffic.

-

New memory in algorithm

His laugh transformed his face. I remember his hands and how strong they were. We’d play catch when I was just a kid and he’d launch the baseball at me as hard as he could. If I showed any sign of fear he’d yell at me or quit and walk away, leaving me standing alone in the street.

I often thought about stabbing him while he was asleep. Even as a four-year-old, I thought it inevitable that my father would kill me, that I’d die violently and his face would be the last I’d see. I grew resigned to the idea and waited.

He bought us tickets to minor league baseball games when I was a kid. We’d go and eat stadium dogs and now and then a foul ball would come our way. Those were the best memories I have of spending time with him, even though I was still afraid. Years later, I got us tickets to a baseball game for his 49th birthday and it was a disaster. He was terribly ill and no longer had strength enough to climb or descend the stadium steps. He didn’t enjoy himself and we left early.

The year before he died he chain-smoked Marlboro Lights. Sometimes I’d sneak down and steal one, ripping the filter off before smoking it. There was never any booze or even beer in his house. He used to listen to Steely Dan and I didn’t appreciate the music until I got older, long after he was gone. It’s a shame we could never really talk about music together, we never got a chance to share our indebtedness to the music we loved.

He only talked about death twice, the first when I asked why he always seemed so depressed. I’d just turned eighteen and graduated high school. I’m dying, he said. Days later he told me to leave, that he wanted to spend time alone with his wife before he died.

-

From the notebooks of T.J. McAvoy

What do the notebooks say about me? The notebooks I’ve discarded, full of words and ideas, the notebooks I’ve kept to stow away in the shadows? They garner dust, the pages yellow and grow brittle. I keep them for no reason, perhaps to prove to myself that my obsession isn’t imaginary, it produces something physical, tangible. And why throw some away and not all of them? What makes me keep a notebook I’ve carried with me for a month, two months, spilling thoughts into it at each available moment, the notebook stained with all attitudes of those stolen moments lost in thought, my hands stained with ink, black, just as the notebook, black, becomes for me the only enduring proof that I have lived this life, here, with everyone else, a walking ghost among the living? What do the notebooks say about me?

-

An Excerpt from the Enlightenment Project [revisited]

I imagine I’m a slave in ancient Rome during the early reign of Octavian. I’m approaching middle age but in fine shape, and my meager education allows me to work as an accountant for a quite reasonable and beneficent consul. I do not know any other life or situation, for I was born into servility and have demonstrated strength and aptitude in my duties. The respect I display and the ethic with which I perform my work has awarded me a sense of freedom and respect from my master and in my community. The Republic is in disarray with the separation of Antony to the Egyptians and the whore Cleopatra. The consuls and the local population all fear the worst, that a total breakdown of the Republic is inevitable. Octavian has begun recruiting a vast naval army and I volunteer, resigning my work as a clerk in hopes of being completely freed after military service. For months I train as the tension tightens and war becomes more of a certainty.

I have no wife, no children, and no family in a world that makes little sense to me. The machinations of man seem to govern all rules of the Earth, for we have truly become rulers of the land. There are no gods and the Republic is full of imbeciles who have nothing better to do than believe in mystic flattery. We are the true gods; the world is a hostile place where men encourage this hostility through politics and war and the perpetuation of enslavement. If I die in Agrippa’s war at least I’ll finally be absolved of this systematic separation of those with privilege and those without. The world is a cruel and barbaric place and the Republic is an ornate façade. I have studied Cicero and believe that a man stripped of the ability to govern his own fate is a gross injustice. So I will fight for my own freedom and nothing more; I shall not grieve if the Republic perishes.

Most other slaves have it far worse than I. They toil and bleed and are murdered for no other reason than for the powerful to assert its control. I observe in silence, grateful for my luck, but am aware that it is luck and only luck that separates the diseased slave from me, only luck that separates the servile from the privileged. Is not man in his status as god the most cruel and unjust?

[painting by Thomas Cole]