Dreams with at least two or three separate but connected pornographic situations/episodes, or more like explicit masturbatory behavior on my part, publicly, in front of acquaintances or family members. Horrifying events. I remember one specific episode in which my brother and his wife sat watching a drama or more like an aircraft display while I lay supine behind them trying (and somehow succeeding) to masturbate with a common household item made of hard plastic. It was like an old camera or something and despite the discomfort I enjoyed it, working toward that familiar light behind the eyelids, intensely aware of my surroundings: a dim planetarium with real (but small) aircraft flying around the stadium (perhaps it was out of doors and the theatre was the world itself), and when I looked up or opened my eyes I saw my brother gazing down upon me over his seat with an expression of ridicule and intense enjoyment and his wife’s expression of satisfaction (not to be confused with nor meant as gratification) for she understood and could identify with perversity despite being wholly rational while I was obviously crazy, purely and openly crazy, and her expression also betrayed a tinge of respect for my having the balls to boldly masturbate around so many people with a foreign object not at all intended for sexual use. I felt extreme embarrassment and the realization that I was caught in the act, my deeds were irreversible and my legacy as a mad pervert firmly cemented, and also that I had painfully shredded some of the skin from my penis during the act and lie there bleeding, mortified. The dream then shifted and I was part of an army and thus had to ensure the safety of the aircraft flying about the theatre, or something like that, which moved the dream into completely different emotional terrain. But for the purposes of this particular moment on this particular page I will adhere to the theme of sexuality, or subconscious masturbation, to be precise. Even aged four years I knew what sexuality was, though there was no word for it, and no words at all, at least those of the read and written varieties. I dreamed often of women three times my age, which made them about 20 or thereabouts, and I particularly dreamed of bare women’s asses. Nothing special about them, no strutting or tail-wagging or any of the other abundant desires wrought of man’s maturity and experience, just women’s asses, bare, by moonlight. Those are the most premature sexual thoughts I can remember having, and I remember they came from dreams and I’d wake up feeling an intense need to do something but not knowing exactly what. Instincts told me that an action had to follow the dream but the act eluded me until few years later. Perhaps those early dreams were a microcosm of or metaphor for all of my dreams, then and now, threatening or otherwise. All dreams force me into one action or another, whether it be choosing to protect a theatre full of airborne aggressors or mutilating my most intimate anatomic module.

Tag: writing

-

De la Pava’s greatness

Sergio de la Pava is a New York attorney. Attorneys don’t normally set out to write novels, and certainly not great ones. Or so it seems. And yet that’s what de la Pava has done. His novel A Naked Singularity, winner of the 2013 PEN/Bingham prize for a debut work, was written in 2008 and published by de la Pava himself. His second novel, Personae, also self-published, was picked up by the University of Chicago Press along with A Naked Singularity after people began to read Singularity and notice how good it was/is.

Writers like de la Pava (I know of none) are anomalous. Publishers and the major houses in particular have created an archetypal (and exclusive) environment based on a specific business model. Literary agents act as middlemen between writers and publishers and it works well enough for the publishers to be able to publish books and still make a profit. Booksellers get paid and the writer gets paid and thus the agent gets paid and everyone is happy. Unless writers object to this model and choose to wade into the publishing world alone and self-publish, which creates all sorts of problems for publishers and sellers.

Naturally the publishers and agents (and even some established authors cemented neatly in the archetypal model) abhor self-publication. It renders their role in the process irrelevant and removes their share. Thus, when a self-published novel written as well as A Naked Singularity comes along and threatens to sell a load of copies, the major houses cry foul and either look to evolve the business model or continue to crusade against artists. Self-published novels are most often unread and become obscure and nonexistent. With A Naked Singularity, Sergio de la Pava has written a novel so undeniably good that he’s managed to circumvent the business model adopted by the major houses, and he’s the first major voice to do so since the model’s metamorphosis into its current state.

De la Pava is a serious talent whose voice commands attention. He’s earned the PEN/Bingham award, and Personae firmly establishes what readers of A Naked Singularity thought to be true: that de la Pava is the rarest of literary surprises, a writer who doesn’t appear to have set out to write a great novel but has, and a writer who can’t help but make his contemporaries envious of his lexicon, his acute intelligence, and his exemplary storytelling ability. He’s a previously unheard-of writer (he’s an attorney, for god’s sake) who puts his contemporaries to shame and whom, if the major houses had their way, wouldn’t have been discovered, wouldn’t have sold nearly as many copies, and wouldn’t have received the attention his talents warrant. At least not yet.

The publishing world would like readers to believe that there are two types of North American writers: those whose works are worth reading, and those whose aren’t. I posit two completely different classes: Writers who aspire to be great, and writers who ARE great. De la Pava is now entrenched in the latter category. His works give hope to readers who also write literature and likewise aim to challenge the limits of ambition, consciousness, and the status quo.

-

Re: Person I never knew

I write letters to people and then forget that I wrote them, only to write them again, obviously in the same hand and with similar affect but with diverging themes and words. I write letters and send them via standard mail, paying twice, sometimes three times for postage and I send letters via electronic mail and forget all of it, as if it never happened. I re-write letters and read them just to ensure that what I’ve written is comprehensible and also to ensure that the words resemble the ideas I wished to portray. Two letters addressed to the same person sit before me and I worry if one of the letters isn’t perhaps mis-addressed. I open the letter and it’s addressed to the correct recipient so naturally I have to check the other letter as well, also addressed to the intended reader. I set the letters next to each other and read through them at the same time sentence by sentence. It’s remarkable, the slight change in ideas I sought to portray, a metamorphosis from inchoate to discernible, the relationship at first solely visual via the symbols on the page. Same hand, same voice, different writer. Different thinker in a different time. The eye and brain form a symbiosis and thus a narrative is traced and if not narrative then the expression of thought and perhaps emotion as illustrated carefully by the author of the letter specifically for its intended recipient. Non-formulaic salutations end in nearly the same fashion (though not quite) and the signatures are mismatched just enough for a shrewd reader to question that both letters were written by the same man, the same hand, the same writer. I fold the letters to re-seal them in envelopes and send them on their way so as to begin to focus on all the letters I still have to write.

-

Write/right/rite

Writers would quit writing if they wrote for the reader. Readers who sit or lie while reading to satisfy something inside, a voice that beckons in whisper (whimper). If the writer cared for the reader and wrote in the best interests of the reader, he/she would quit writing and instead pick up the pen as a weapon in defense of the reader, to subdue the approaching monsters, namely literature and other writers who have not yet surrendered the pen for the sword, because the writer who writes with the reader in mind writes (different from the previous verb but nonetheless a verb that shall heretofore be referred to as write) for capital gain and fame, which are both diametrically opposed to literature, except in extreme circumstances. Writers are most often broke and unwilling to write for the reader and instead cater to that obsession within, not a voice, not a whisper nor a whimper but a commanding shout with a throat hoarse and desperate and maligned. The writer (among the rest of the world) knows that writing is not lucrative, again, except in extreme circumstances, and the writer does not care, just as he/she does not care for whom, if anyone, ever, will read what they write. The words beckoned forth from caverns deep and resoundingly unique, the only true self, the unadorned self, the self wrapped tightly (safely) in the selfsame ideas that will ultimately destroy the self. This self obliges willingly, acutely aware of the danger and ecstasy involved.

-

Re-immersionalist

Perhaps I should manage my time better, become a minimalist, an incrementalist, a fractalist, a post-modern deconstructionist, for there is always so much to accomplish in one day, and so the days adhere to form an unbreakable chain upon waking from the banality and the obligation and rote pattern of it all; when we re-immerse the self back into the ever-changing world we find new patterns that must be mastered, and soon, for there is no time to waste.

-

Luna silenciosa

The moon is full and white and he watches it hang static and alone in the sky like a beacon to worlds ancient and afar. A breeze warm and comforting carries the cigar smoke away from his face and he breathes in the night air, floral, dense, fecund. Wade is at relative peace, adrift in the cosmos. Crickets and other night insects shriek in rhythm from the shadows. Direll jumps over the back fence and ambles toward Wade in the moonlight, his hand raised in greeting.

How’s your eye? Wade says.

Still cain’t see shit out of it.

Direll sits next to Wade and exhales deeply. He takes a plastic lighter from his shirt pocket and lights a joint. Wade puffs his cigar and the men sit silent listening to the crickets and also sounds they can’t hear.

Pretty moon tonight.

Reminds me of when I was a kid, Wade says.

How so?

Not sure. Stimulates something vestal, I think.

Vestal?

Maternal, maybe.

The men are silent.

Beautiful, though, Wade says.

Yeah.

Seen your Comanche pal tonight? Direll asks, smiling. He puffs long and deep on the joint and blows out what appears to Wade to be an impossible quantity of smoke, a long uninterrupted ribbon.

He’s Patwin. And no.

Insects resound in the thicket of brush to their left. The sky is open to everything. The sliding door slips open and the boy peeks out at them.

Can I play one more before bed? he asks.

Say hello to Direll.

Hi Direll.

Hello champ.

One more round of what? Wade asks.

Death Membrane.

Death Membrane, Direll repeats, looking out over the yard as if out at sea or as if he could see the words there in the half-light. As if the words or the game itself fashioned up from the underworld or vapor. The joint is tucked away out of the boy’s view.

One more round, Wade says, and the boy is back inside.

The men are silent and the moon glows as if from within and Direlle exhales sharply and says, You watch that game tonight?

Wade looks at him and puffs his cigar. No, he says. I was reading.

What you reading now.

Wade puffs on the cigar and says, Fukuyama.

Fukuyama, Direll repeats, nodding, staring at the yard again and the shadows therein.

Then they’re silent for many minutes, both of them chasing certain and uncertain thoughts. Direll tosses the roach into the grass and sighs. He says, Brother, I got to be going.

Wade watches his neighbor walk to the fence and climb over. He looks up at the moon and stares at it, wondering about it. He tamps out his cigar and stands and walks inside, the crickets announcing his departure.

-

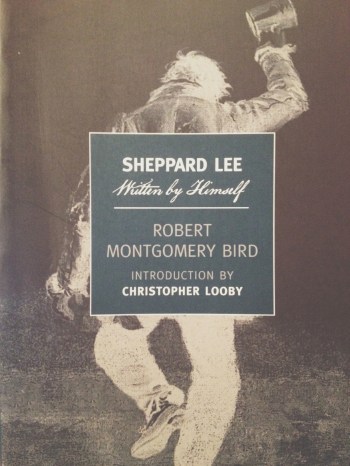

Sheppard Lee: A study in Contradiction [Review]

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness …[1]

Robert Montgomery Bird was 30 years old when Sheppard Lee was published. He’d had plenty of time to scrutinize the human condition, its psychology, and its reaction to and formulation of political structures. He observed the American men and women of his time, the deep social rifts between them, rampant envy and resentment resulting from their differences. He saw the social division as a natural reaction to the American structure, an inherent flaw in the ideals of the Constitutionalists. What resulted, according to Bird, was a society of longing, a desire to strip away one’s identity in search for another. In Sheppard Lee, Written By Himself, published by the acclaimed NYRB Classics, Bird explores these topics and castigates them with comic, satirical brilliance.

When Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, he and the Constitutionalists had in mind a particular end for the individual in a democracy. The idea was to give each individual the right to become their own end via the means they chose for themselves. The rich and the poor alike were given the political freedom to follow their dreams, to self-sustain beneath the umbrella of U.S. government protection. These were the ideas wrought from the Enlightenment, from hundreds of years of political and moral theory, and it was considered to be the best government structure—in principle and practice—in the history of the world. The policies were meritocratic and experimental in nature, molded from the idea that there is no nobler role of government than to allow its citizens the opportunity to safely and responsibly forge their own path in the world.

But what Jefferson and the other Constitutionalists failed to account for was the huge rift that would be created between the rich and poor, “a political complexion […] founded in, and perpetuated by, the folly of the richer classes.”[2] The economic structure was fashioned from the principle of equal opportunity, but what resulted was the rich becoming richer and the poor becoming poorer. Soon the opportunities of the wealthy greatly outnumbered those of the impoverished. This great division among people that were supposed to share an equal place in society created disparate perceptions: “The poor man in America, feels himself, in a political view, as he really is, the equal of the millionaire; but this very consciousness of equality adds bitterness to the actual sense of inferiority, which the richer and rather more fortunate do their best […] to keep alive.”[3]

This situation cultivated a deep and pervading sense of longing unto the poorer classes, the immigrants, the African-Americans. It was a hypocrisy that spawned indignation, for certain injustices were happening in America, the land where every man was supposed to be self-evidently equal, where this sort of unfairness ought not to have been happening. Citizens on the unfortunate side of the socio-political structure were cast further out, excluded from the decision-making process, left only to appeal, “Why should the folly of a feudal aristocracy prevail under the shadow of a purely democratic government?”[4] They found themselves wishing more and more to inhabit the lives of the privileged, hoping to inherit their advantages. The character of Sheppard Lee finds a cosmic loophole where this is actually possible for him, and what results is an absurd waltz into the American psyche where nothing, including the principles of his country, is what he thought it would be.

Slavery was obviously another American hypocrisy. In a land where all men were supposed to have legitimate opportunities for freedom and the American ideal, certain men and women were being bought and sold, treated sub-humanely, their happiness stripped from them before they had a chance to obtain it. To be a slave was to be “the victim of fortune, […] the exemplar of wretchedness, the true repository of all the griefs that can afflict a human being.”[5] These are not descriptions of equality. Bird was aware of the hypocrisy around him. He knew that the real America was a blatant contradiction to the ideals penned in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights. Sheppard Lee is Bird’s response to what he observed. It’s an attack on the life around him, highlighting the absurdities in order to draw attention to them, a picaresque adaptation of reality.

e He The hypocrisy of the political structure birthed a certain behavior in its citizens. It provoked lasting looks of envy from the poor onto the rich, from the slave unto the free man, it widened the gap between neighbor and friend. It forced people into constant comparative qualification. Equality of opportunity naturally evolved into a sort of Darwinian culture where the weaker or less qualified individuals were exploited by those gaining power with each business day, each acquisition. The character of Sheppard Lee is a symbol of the common American man. He is constantly in pursuit of curing what ails him, namely his imperfections, his insecurities. He feels that the only way to do this, once he has figured out his ability to occupy the bodies of the dead, is to seek out those unfortunate dead whose lives seemed to be better or happier than his. Lee is thus vicariously the jolly hunter, the playboy, the rich man, the morally perfect human being.

As the philanthropist character in Book V begins to see his life of charity and compassion unravel before him due to the ingratitude of his fellow men, he states rather profoundly that “man is an unthankful animal, and of such rare inconsistency of temper, that he seldom forgoes the opportunity to punish the virtue which he so loudly applauds.”[6] One could read this passage straightforwardly as it applies to the narrative, or they could also read it as an analogy about the duplicity in the principles of the United States that Bird observed and attacked. At this point in the book, the reader is well aware of Bird’s pattern of disappointing Sheppard Lee’s efforts at finally becoming content with who he is, whoever that may be. The fact that he is repeatedly upset in his effort to find happiness by infiltrating the body of the most morally pure dead person he could imagine leaves him to believe that, “I had experienced in my present adventure […] doubts as to the reality of any human happiness.”[7]

Bird had keen observational skills to see the contradictions between those engraved in the United States Constitution and the actual daily social rigors in young America. But these things could have been seen even by those who chose to turn their attention from them. I might even make the argument that the rift between the haves and the have-nots is today considerably wider than in Bird’s America.

The novelist’s value in a society is his or her ability to shape and influence the culture. Bird did this by drawing attention to the inconsistencies in his society, pointing the finger at the innate hypocrisy in American idealism. He saw the way social stratification affected the individual in society and diluted their notions of identity, how it forced them to look at others in either envy or disgust. In Sheppard Lee, Bird exercised his acute understanding of the impractical democratic experiment and its effects, primarily the “political evils which demagoguism, agrarianism, […] and all other isms of vulgar stamp [it] brought upon the land.”[8]

What we see in Sheppard Lee, through Bird’s narrative about the blurred notion of identity, is a man chasing his preconceived notions of happiness, jumping from social status to social status in the pursuit of happiness, only to find something wrong, something to lament about his new body and personage with each new identity. It is a narrative both funny and sad, both audacious and absurd, and at times a promotion of prejudice as equally contradictory to the truth as Bird’s America.

[1] Jefferson, Thomas, in Koch, Adrienne. The American Enlightenment. George Brazillier Press, New York, 1965, 378. [2] Bird, Robert Montgomery. Sheppard Lee, Written By Himself. New York Review of Books, New York, 2008, 305. [3] Bird, 306. [4] Bird, 306. [5] Bird, 332. [6] Bird, 271. [7] Bird, 304. [8] Bird, Robert Montgomery, 306.

-

Yearning

When I left the library rolling skies befell the world and rain boiled downward from molten clouds sending pedestrians and anyone not under cover of shelter skittering into shadows beneath dripping awnings or back into campus buildings to avoid the onslaught of water and hail the size of human eyes hard as rock and jaggedly imperfect. I made it to the car gasping and wild in the eye with the books stuffed up into my jacket to keep them dry or as dry as possible with water pounding the roof of the car and sliding down the windows in cascades of prismatic light and sound. A strange sense of isolation and security overcame me and it was warm in the car, the windows began fogging almost immediately from the moisture in my clothes, in my hair. I sat there a long time listening to the rain reclined in my seat, eyes closed, trying to immerse myself into the water, trying to imagine myself in each ounce, in each drop of water and ice from the sky and the storm would surge and then taper off, surge and taper off, rhythmic serenity, a paroxysm of peacefulness. I could die right now, I thought, even though it was the first time all day I hadn’t yearned to die. The rain slowed and eventually stopped and again I felt part of the world, less secure, exposed afresh to the discrimination of energies and of the minds of all the people of the world and I started the car and pulled into traffic.