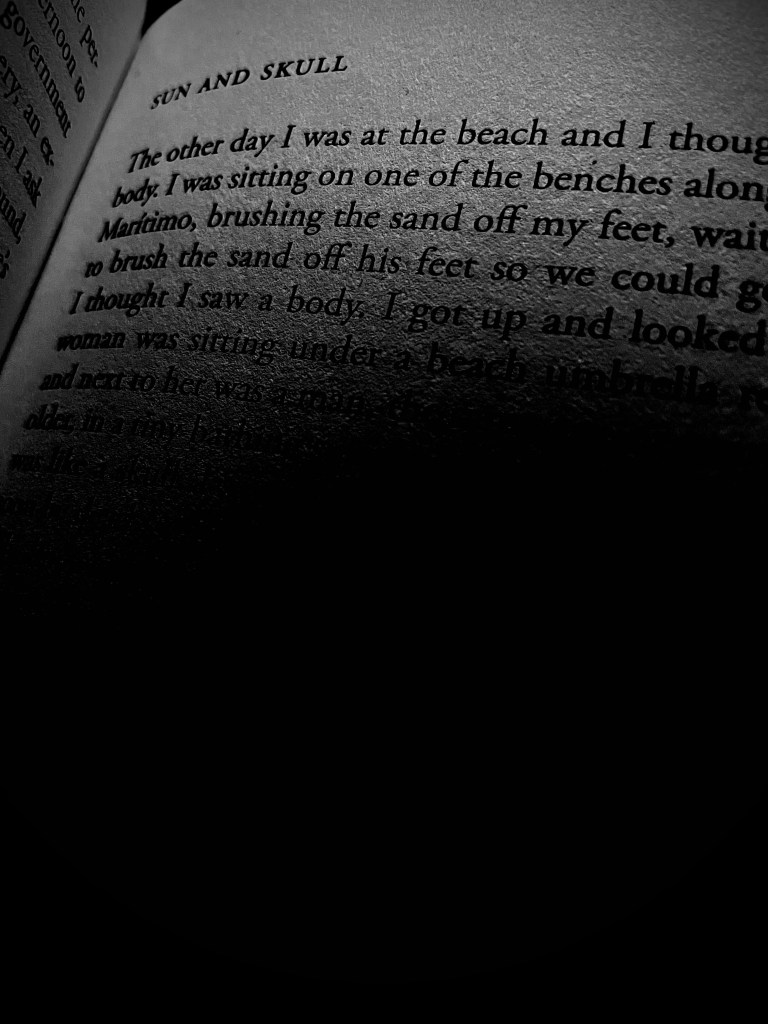

The other day I was at the beach and I thought I saw a dead body. I was sitting on one of the benches along Blanes’ Paseo Marítimo, brushing the sand off my feet, waiting for my son to brush the sand off his feet so we could go home, when I thought I saw a dead body. I got up and looked again: an old woman was sitting under a beach umbrella reading a book and next to her was a man, the same age or maybe a few years older, in a tiny bathing suit, lying in the sun. This man’s head was like a skull. I saw him and I said to myself that he would soon be dead. And I realized that his old wife, reading peacefully, knew it too. She was sitting in a beach chair with a blue canvas back. A small but comfortable chair. He was stretched out on the sand, only his head in the shade. On his face I thought I glimpsed a frown of contentment, or maybe he was just sleeping while his wife read. He was very tan. Skeletal but tan. They were tourists from up north. Possibly German or English. Maybe Dutch or Belgian. It doesn’t really matter. As the seconds went by, his face looked more and more skull-like. And only then did I realize how eagerly, how recklessly, he was exposing himself to the sun. He wasn’t using sunscreen. And he knew he was dying and he was lying in the sun on purpose like a person saying goodbye to someone very dear. The old tourist was bidding farewell to the sun and to his own body and to his old wife sitting beside him. It was a sight to see, something to admire. It wasn’t a dead body lying there on the sand, but a man. And what courage, what gallantry.

Bolaño, Roberto, Between Parentheses: Essays, Articles, and Speeches, 1998—2003. Trans by Natasha Wimmer. New Directions Books, New York, 2011: 157.