Some writers have so confounded confused society with government as to leave little or no distinction between them. They are not only different but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants interactions and government by our wickedness laws. The former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections innovation and collaboration, the latter negatively by restraining our vices inspires subservience or rebellion. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first is a patron, the last a punisher.1

Government of our own is our natural right. And when a man seriously reflects on the precariousness of human affairs, he will become convinced that it is wiser and safer to form a constitution uphold American democracy of our own in a cool, deliberate manner rather than trust such an event a necessity to time and chance. If we don’t, some Massenello the populist fascists will arise, laying hold of popular disquietudes to collect together the desperate and discontented, and by assuming to themselves the powers of government, may sweep away the liberties of the continent like a deluge. Should the government of America return again into the hands of Britain the kleptocratic Republican regime, the tottering situation of things will be a temptation for some desperate adventurer billionaire to try his fortune.2

**

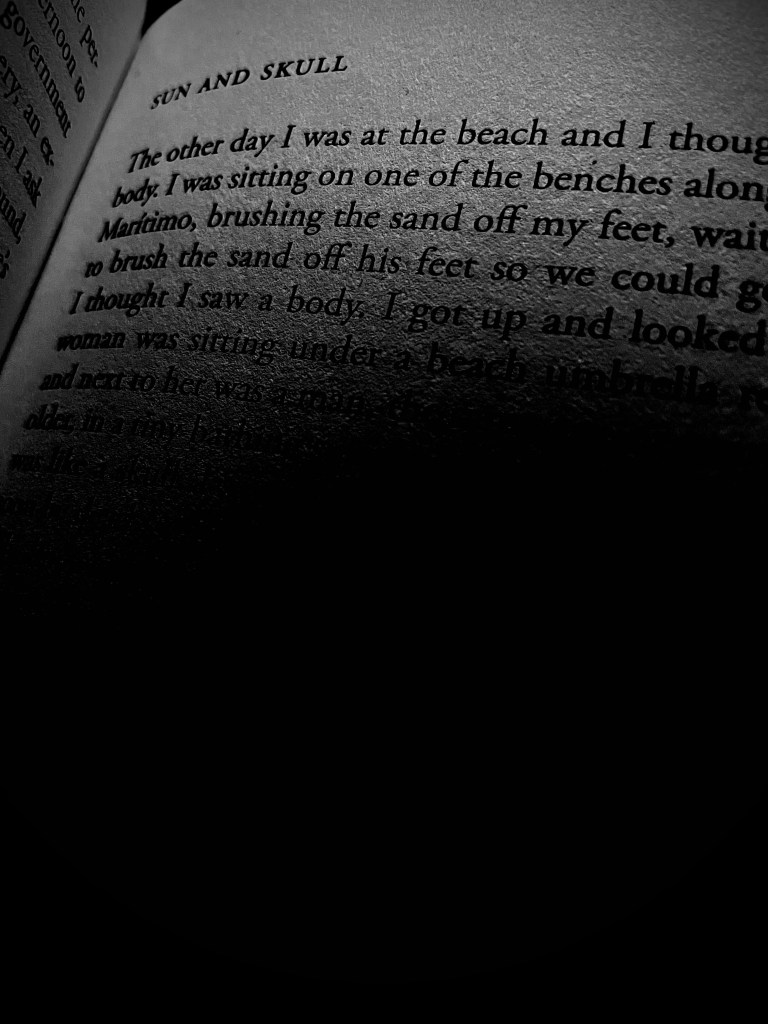

To talk of friendship with those in whom our reason forbids us to have faith […] is madness and folly. Every day wears out the little remains of kindred between us and them. […] You that tell us of harmony and reconciliation a new great America, can you restore us to the time past of our shared interests? […] Neither can you reconcile Britain right-wing fascist traitors and the un-treasonous majority. The last cord has been broken, the people of England criminals of the failed coup attempt of January 6 and the Republican regime sweeping it into the margins of history are presenting addresses against us. There are injuries that nature cannot forgive; she would cease to be nature if she did. Just as the lover can’t forgive the ravisher of his mistress can the continent we forgive the murders of Britain traitorous failures who stormed the capitol. 3

I have never met a man either in England or America a blue or red state who did not confess his opinion that a separation between the countries us would take place one time or another was inevitable. And there is no instance in which we have shown less judgment than in endeavoring to describe the rightness or fitness of the continent for independence maintain the health and vigor of American democracy. As all men vary only in their opinion of the time, let us, in order to remove mistakes, take a general survey of things the American sociopolitical landscape, and try to find out the very time. We need not go far, the inquiry ceases at once, for the time has found us.4

Taking up arms merely to enforce a pecuniary law seems unwarrantable by divine law the social contract, just as is the taking up arms to force obedience to that law. […] The lives of men are too valuable to be cast away on such trifles. It is the violence done and threatened to our persons, the destruction of our property by an armed force police, the invasion of our country communities by fire and sword federal officers, that qualifies necessitates the use of our own arms. The instance when such a defense becomes necessary, all subjection to Britain federal law will cease and the independence defense of America should have been will be considered upheld, as dating its era from and published by the first musket that was fired against her. This is a line of consistency neither drawn by caprice nor extended by ambition but produced by a chain of events of which the colonists un-treasonous USA majority were not the authors.

I shall conclude these remarks with the following timely and well-intended hints: We ought to reflect that there are three different ways by which independence the USA’s future may hereafter be effected, and that one of those three will one day or another be the fate of America.:

- By the legal voice of the people

in Congressvia fair election processes - By

a military powerenemies from without - By a mob from within5

Volumes have been written on the subject of the We are engaged in a struggle between England and America the traitorous few and the majority. Men Citizen defenders of Democracy of all ranks have embarked on the controversy, from different motives and varying designs must be aware and prepare. […]6